The island at the center of the artificial intelligence boom—and increasingly the global economy—lies on geological and geopolitical fault lines. Taiwan, the producer of most of the world’s advanced semiconductors, faces intensifying pressure from mainland China and growing uncertainty about US support. War doesn’t appear imminent. If it were to erupt, though, the shock to the global economy would be seismic.

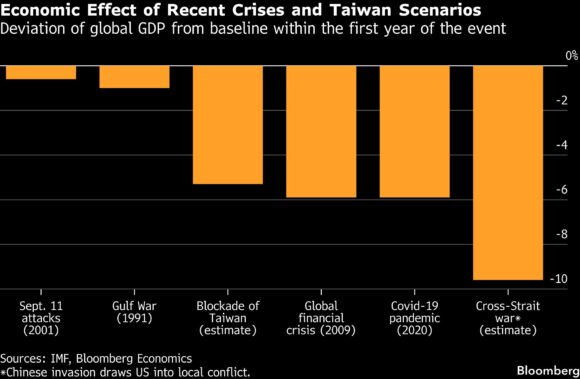

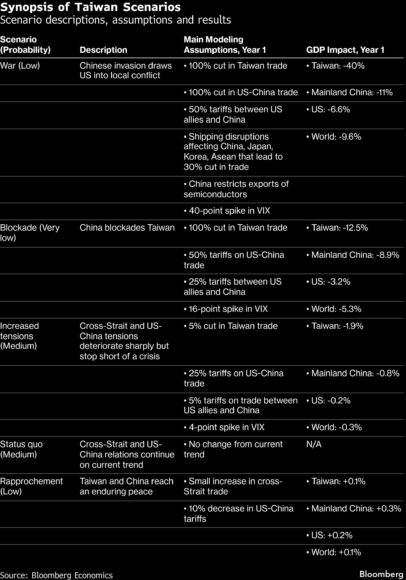

In this report, Bloomberg Economics sets out five possible paths for how tensions in the Taiwan Strait could unfold—from war to rapprochement—and models their economic impact. In the most extreme case, a US-China conflict over Taiwan would cost the global economy about $10.6 trillion, roughly 9.6% of global gross domestic product, in the first year alone, eclipsing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the 2007-09 global financial crisis.

• A US-China war over Taiwan would severely curtail the world’s access to logic semiconductors, the essential input for everything including cars, planes, AI data centers and smartphones.

• Trade between the two superpowers and their closest partners would likely collapse. Shipping through one of the world’s busiest sea lanes would grind to a halt. Global markets—increasingly dominated by bullish bets on AI—could crater. Industries dependent on Taiwan’s chips, including smartphones, PCs and autos, would be severely affected.

• The damage would be global. Taiwan’s economy would be decimated. We estimate China’s GDP would fall by 11% and the US’s by 6.6% in the first year. In addition to the main actors, the European Union could have GDP drop by 10.9%, India by 8% and the UK by 6.1%. Closer to the fighting, South Korea could shave 23% off GDP, and Japan 14.7%.

• There are other potential outcomes. The Chinese government might try to coerce Taiwan through blockade. Or, in an optimistic but unlikely scenario, both sides could move toward detente.

High Stakes in the Taiwan Strait

The semiconductor shortages that hit as the world reopened from 2020 Covid lockdowns underscored how essential chips are to the global economy. A crisis in the Taiwan Strait would deliver a much greater shock.

Taiwan makes 62% of the world’s most advanced logic semiconductors and is a key manufacturer of legacy chips as well. Globally, 5.3% of value-added production is in sectors using chips as direct inputs into production, or almost $6 trillion.

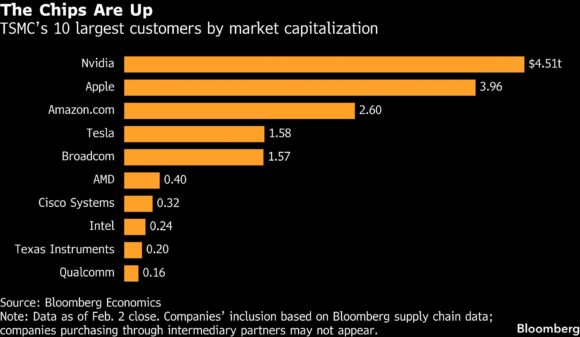

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) accounts for 70% of global foundry revenue, powering customers such as AMD, Apple, Broadcom, Nvidia and Qualcomm. Taiwan’s semiconductor production isn’t just TSMC. Companies including UMC and PSMC are major names in mature-node manufacturing, anchoring the island’s strength in automotive, industrial and consumer chip supply.

That dominance translates to financial markets. The largest US tech companies account for more than 30% of the S&P 500, fueling the lion’s share of market gains in recent years. Total market capitalization for the top 10 customers of TSMC, the island’s chips champion, is $14 trillion.

The Taiwan Strait is also a critical artery of global commerce. Almost half the global container fleet and more than one-fifth of global maritime trade ($2.45 trillion) passed through the waterway in 2022.

Strategically, Taiwan is a frontline test of US power and credibility in Asia: If Washington blinks, allies from Seoul to Canberra will take note. It anchors the First Island Chain, the arc from Japan to the Philippines regarded as a check on China’s military reach. And, politically, its 23 million citizens sustain a thriving democracy—a symbol of what’s at stake in the broader contest between open and authoritarian systems.

Breaking the Status Quo

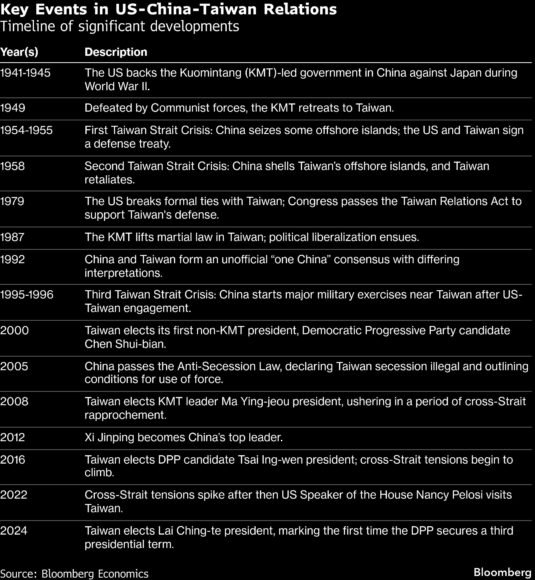

In 1979, when the US cut official ties with Taipei to establish them with China, many assumed China would absorb Taiwan. Instead, an uneasy status quo took hold, supported by four pillars: US military superiority and ambiguous commitment to Taiwan’s defense, Beijing’s strategic patience on unification, Taipei’s balancing act on its identity and relationship to China, and deepening cross-strait economic and cultural ties.

Those pillars are crumbling. The US no longer holds a decisive military advantage over China. Beijing is growing less patient about achieving unification on its terms—and more capable of forcing the issue. And Taiwan’s democracy now defines an increasingly distinct identity.

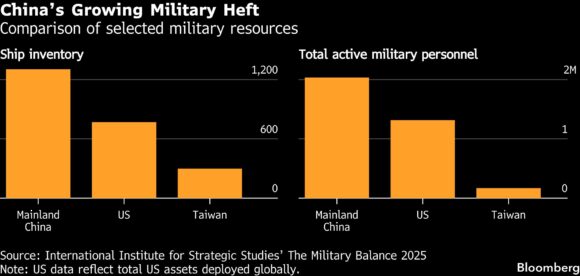

In 1996, during the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis, the US sent an aircraft carrier through the strait, a muscular signal to China. The same gesture would carry far less weight today, when China has three aircraft carriers of its own and stockpiles of ballistic missiles known informally as “carrier killers.” Together, they underscore how far the Chinese government has come in modernizing its military, transforming it into what the Pentagon recognizes as a near-peer force.

China has surpassed the US in building the world’s largest navy—critical for projecting power across a strait or blocking other navies from approaching it. Even in the realm of undersea warfare, where the US has historically held the advantage, China is on track to have the larger submarine fleet by 2030-2035.

Geography also favors China. In any conflict over Taiwan, China’s forces would be fighting in their own neighborhood, while US ships and aircraft would have to traverse thousands of miles, stretching supply lines and complicating operations.

China’s advanced capabilities include stealth aircraft and hypersonic missiles, and it’s rapidly expanding its edge in other domains. The government has invested heavily in counter-space and offensive cyberoperations designed to exploit US vulnerabilities and dependence on space-based systems.

China’s vast industrial base allows it to manufacture ships, missiles and other weapons on a faster and larger scale than the US, suggesting it could sustain a high-intensity conflict longer, even while taking significant losses.

The comparison with Taiwan is even more striking: In 2003 the Pentagon assessed that even though China’s army had a numerical advantage over Taiwan’s, the island’s air force and navy maintained a qualitative edge over China’s. Today, China’s military has an overwhelming advantage in quantity and quality.

The View From Three Capitals

In 1950, China was rebuilding from years of war, Taiwan was under martial law dreaming of retaking the mainland, and the US was determined to anchor its power in Asia. Three-quarters of a century later, the ambitions of each country have shifted significantly.

China considers itself stronger than ever and is increasingly impatient for unification. Taiwan is committed to a distinct identity rooted in its democracy. The US, weary from decades of war and anchoring the global order, is questioning the scope of its commitments abroad.

Since taking power, Chinese President Xi Jinping has intensified pressure on Taiwan. Like his predecessors, Xi frames unification as central not only to his legacy but also to the Communist Party’s legitimacy and China’s rejuvenation. He views the government’s past focus on economic incentives as a failure and has increasingly turned to more coercive measures, including ramping up military activity around Taiwan, luring away its remaining diplomatic allies and blocking its participation in international forums.

Although he’s China’s most powerful leader in decades, Xi still faces constraints: a slowing Chinese economy, a largely untested military still grappling with corruption and a challenging international environment defined by an unpredictable and often unfriendly US. Those cabin his ability to pursue even tougher policies toward Taiwan—for now.

From Xi’s perspective, Taiwan is slipping further from China’s orbit, a view reinforced by repeated electoral victories of the traditionally pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party and by polls showing most residents identify as Taiwanese rather than Chinese. The DPP, now led by President Lai Ching-te, has largely stopped short of pushing for formal independence, but it remains deeply wary of the Chinese government and committed to preserving Taiwan’s status quo.

Despite public skepticism toward China, Lai’s administration faces steep political constraints. The DPP lacks a mandate to pursue major defense-spending increases or reforms needed to bolster deterrence across the strait. The opposition Kuomintang (KMT), which favors more engagement with Beijing, controls the legislature and has resisted higher defense budgets. Many voters prioritize social spending over military buildup and prefer shorter conscription, leaving Lai with little room to prepare for conflict.

Complicating matters further is an unconventional US president who has questioned the logic of defending Taiwan. During his 2024 campaign, Donald Trump suggested Taiwan should “pay insurance” for its defense. Now back in the White House, he’s reverted publicly to the traditional US stance of “strategic ambiguity,” avoiding explicit commitments. There’s little reason to think that his personal skepticism has faded.

Historically, the US Congress has anchored the government’s commitment to Taipei, maintaining a security backstop even as the executive branch cut official ties. Now, with Trump’s Republican allies dominating Congress, it’s unclear whether lawmakers would resist any effort to scale back US support.

The result: an increasingly unstable status quo and higher tensions across the Taiwan Strait. Since Lai’s inauguration, our Taiwan Security Index, which gauges geopolitical friction through Chinese military activity and official rhetoric, has risen markedly compared with the previous two years—even as it remains below the peak from around August 2022, when US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan. Frequent flights by Chinese warplanes into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone are a visible, and unsettling, marker of how tense the situation has become.

Does this mean war is imminent? Probably not. China’s military is making steady progress toward possessing the capability to take Taiwan by force, but the government likely still views an all-out attack as too risky, at least for now. China could probably overwhelm Taiwan’s defenses, but a US intervention—assuming it comes—could deny China victory. A failed invasion would be a catastrophic blow for a Communist Party that’s staked its legitimacy on unification.

Even so, the risk of conflict is moving only one way: up. As China gains strength and Taiwan appears to drift further away, Beijing’s patience is fraying. And as Chinese and Taiwanese forces operate in ever-closer proximity, the danger of a misstep igniting something larger grows.

Scenarios for the Taiwan Strait

We outline five pathways for cross-strait relations over the next five years, ranging from a Chinese invasion that draws the US into conflict to rapprochement between Taipei and Beijing. For each scenario, we use a suite of models to estimate GDP impacts across major economies and globally through three channels: semiconductor supply chain disruptions, trade shocks from shipping disruptions and sanctions, and financial market shocks.

Supply chain disruptions are assessed using the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s trade in value-added data for 2022. We first estimate chips shortages and the direct hits to sectors that use semiconductors as inputs: computers, electronics and optical products; electrical equipment; machinery and equipment; motor vehicles, trailers and semitrailers; and other transport equipment. We then use OECD input-output tables to estimate spillovers to other sectors—for example, weaker metal output if auto production slows.

Estimates of semiconductor production capacity by origin and of risks to the broader semiconductors value chain draw on Bloomberg Intelligence and on research by the Boston Consulting Group and the Semiconductor Industry Association (2024). Based on production capacity data as of 2024, losing access to Taiwan’s production would cut global supplies of cutting-edge logic chips by 62% and less-advanced chips by 31%.

In the war scenario, we assume that China also halts its own exports, removing 32% of global mature and legacy chip capacity. Under this scenario, export controls, shipping disruptions and lost access to Taiwanese materials and packaging further disrupt production in China and elsewhere, intensifying shortages.

Supply chain experts use the term “golden screw” to describe a critical component without which production grinds to a halt. Our war and blockade scenarios capture this dynamic, assuming output in chip-using sectors falls in line with the drop in chip supply.

Under a blockade, curtailed access to Taiwan’s chip production cuts output for advanced electronics such as smartphones by 60%, and for sectors using lagging-edge chips, including autos and home electronics, by 30%. Under a war scenario—when export controls and shipping disruptions compound the shock—production outside China falls 75% for advanced electronics and 65% for other sectors. China’s export controls cushion the hit to its own industry, but supply chain disruptions still lead to a 30% shortfall in chips hitting manufacturing production.

Outcomes could vary. Stockpiling of chips and materials could soften the blow. Reliance on irreplaceable Taiwan-made chips could worsen it. In an extreme case, if production across all chip-dependent sectors halted, the global GDP hit in a war scenario would exceed 15%.

Trade shocks take two forms: sanctions between China and the US and its allies; and, in the war scenario, shipping disruptions tied to military action. We define US allies based on trade shares, treaty ties and judgment: Australia, Canada, the European Free Trade Association, the European Union, Japan, Mexico, South Korea and the UK.

If the US and China are fighting, we assume they’re not trading. We model that as a 100% drop in US-China trade. In the blockade scenario we assume 50% bilateral tariffs. In the heightened tensions scenario we assume 25%. US allies also curtail their trade with China, imposing 50% tariffs in a war, 25% tariffs in a blockade, and 5% tariffs in the increased tensions scenario. China retaliates proportionately. Instruments of economic statecraft are many and varied, including financial sanctions, export bans and investment restrictions. We use tariff shocks as a proxy.

To capture shipping disruptions, we assume a hit to port capacity in China, Japan, Korea and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean). To translate these port disruptions into trade shocks, we build on Verschuur, Koks and Hall (2022). They use a large-scale global maritime transport model to estimate the share of each bilateral industry-level trade flow that’s exported out of, transshipped through or imported into a given port. Those estimates are available for about 200 countries or regions, 11 industries and 1,380 ports. By filtering this dataset for the ports in the war scenario, we have information on which global trade flows are affected by those disruptions.

We estimate the impact on activity of trade disruption at the industry level using OECD trade in value added data, focusing on how lost exports for different products affect domestic production. These demand shocks are combined with semiconductor supply shocks—retaining only the larger shock for each industry—and aggregated to derive GDP effects.

Financial shocks are estimated using a structural Bayesian Global VAR model (Bock, Feldkircher and Huber, 2020), augmented with log real equity prices following Mohaddes and Raissi (2020). We model financial uncertainty as a global VIX shock: five standard deviations in a war scenario, similar in scale to the spike after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and two standard deviations under a blockade. Given heavy market exposure to AI optimism and Taiwan’s central role in chip production, a Taiwan Strait crisis could trigger a larger financial shock than our model implies.

In Case of a War

There are many possible flash points for conflict. One stands out. If Beijing thinks Taiwan is on the verge of declaring independence—or taking other steps that would ensure its permanent separation from China—Chinese leaders could initiate a full-scale assault, despite the risks.

The Chinese government’s caution about an invasion and the range of tools it can use to pressure Taiwan short of war keep the probability of this scenario low for now. But as China’s capabilities expand, and tensions in the strait intensify, so will its readiness to wield them.

Here’s how a Chinese invasion of Taiwan could play out:

The opening assault could come with limited warning. Although China would need to mobilize significant forces to assemble an invasion fleet, it could conceal that mobilization or conduct it under false pretenses. China’s frequent military activity near Taiwan, the thousands of missiles it already has within striking distance and the opacity of its decision-making further fuzz the radar.

China would probably begin with a massive strike campaign on Taiwan and potentially on nearby US forces and bases to keep Washington from joining the fight. Such strikes could erode US military capability but may backfire by pulling the US and allies that host US forces, such as Japan, into the fight.

Taiwan’s density means many military targets sit near key economic hubs. Even with precision targeting, collateral damage to Taiwan’s semiconductor fabrication plants may be unavoidable. China would probably strike with massive cyberattacks against Taiwan or sever undersea cables to disable critical infrastructure, cutting utility access to fabs. Engineers may also be reluctant to work while the island is under siege.

The Chinese government would likely blockade Taiwan to prevent escape or reinforcement. That would halt exports from the island, choke off its access to key supplies and paralyze shipping through the Taiwan Strait.

A US intervention isn’t guaranteed, but if it came, it would likely lengthen, escalate and expand the fighting. Without US support, Taiwan’s defenses would probably be quickly overwhelmed. With it, the island could resist far longer, turning what Beijing would want to be a short, decisive campaign into a protracted conflict.

US and Chinese forces would likely battle for control of Asia’s key sea lanes, further snarling maritime trade. A war between the US and China would almost certainly trigger an economic rupture, with both sides severing trade and investment ties and pressing allies to do the same.

Given the number of variables, it’s impossible to predict with confidence how long such a conflict would last. Taking account of the intensity of fighting, Taiwan’s limited geographic depth and limited stockpiles (particularly on the US side), a few months appears plausible. For simplicity, and comparability with our other geopolitical reports, we calculate it as a year.

This scenario assumes the conflict stays contained within the Asia-Pacific, that neither the US nor China strikes the other’s homeland and that nuclear weapons remain off the table. In reality, a US-China war would carry significant risks of escalation along all these fronts, and a clear victory for either side would be far from assured.

For the main actors, other major economies and the world, the economic fallout in this scenario is catastrophic. Taiwan’s economy is decimated.

We assume a 40% hit to GDP based on losses seen in other modern conflicts.

China suffers a severe blow. With trade ties to major partners cut and disrupted access to Taiwan’s semiconductors rippling across its manufacturing sector, GDP takes an 11% hit. The electronics, autos and machinery sectors directly exposed to chip shortages are the most severely hit. The Chinese government would probably boost defense spending to support the war effort, which could cushion the blow.

Farther from the frontlines, the US still takes an economic hit. Supply chain exposures—through companies like Nvidia and Apple—drag GDP down 6.6% after one year. The blow could be bigger, for two reasons. First, our estimates don’t take account of disruptions to supply of critical minerals or magnets and other derivative products, which are heavily dependent on Chinese production and would likely be subject to immediate export bans. Second, US financial markets and capital spending are heavily leveraged to AI optimism. With Taiwan’s fabs offline, a market crash and slump in investment could add to the costs, relative to our model estimates.

Global GDP after one year is down 9.6%, more than the impact of the global financial crisis or Covid pandemic. South Korea, Japan and other East Asian economies—all exposed to the electronics supply chain and facing severe shipping disruptions—are among the most impacted.

For global businesses, semiconductors are a crucial input and the Taiwan Strait an important trade route. The consequences of a crisis could be wide-ranging. To illustrate that, Bloomberg Intelligence explores the sector-level impact across electronics, autos and shipping.

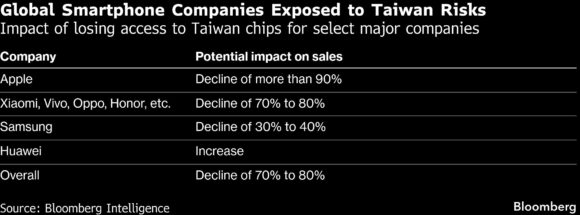

Apple faces the highest systemic risk among smartphone makers, as the island is the only production center for the advanced process nodes critical to the iPhone. Lost access to those nodes could cost Apple more than 90% of its iPhone sales, with global smartphone sales plunging as much as 80% once channel inventory is washed out. Huawei’s self-sufficient supply chain provides a degree of insulation. Samsung benefits from producing about a third of its mobile processors in-house. Xiaomi, Vivo, Oppo, Honor and Android peers could suffer, as TSMC makes most of the chips that they purchase from Qualcomm and MediaTek.

The global PC market could show relative resilience, yet would still face a 30% to 40% revenue hit, as both Apple and Advanced Micro Devices would lose access to TSMC-made chips. Intel, with more than 70% of the PC processor market, might help narrow the gap. Suppliers in Japan or South Korea could step in to fill any void in its substrate sourcing from Taiwan, although shipping disruptions and trade tensions with China could constrain their ability to fully scale up.

Trade embargoes are not included in these calculations but would compound and exacerbate the costs.

About 18% of global automakers’ semiconductor needs are fulfilled by Taiwan. Taking German companies as an example, that would put up to 1.9 million vehicles at risk for BMW, Mercedes-Benz and Volkswagen in 2026. Exposure falls to about 1 million units in 2030, as advanced-node production expands in the US and Europe. Battery-electric vehicles rely heavily on mature nodes of 28 nanometers or larger, which are more easily replaced globally than the 5nm or less nodes produced mainly by TSMC and Samsung for autonomous-driving functions.

Container shipping could sustain a punishing blow. Evergreen, Wan Hai, Yang Ming and Taiwan’s other container shipping carriers could come to a standstill. Cosco Shipping, China’s dominant liner, risks losing 63% to 68% of its revenue, based on its exposure to various trade lanes. Leading South Korean liners such as HMM could suffer a 38% to 43% revenue loss. Japanese liners, including NYK, Mitsui OSK and K-Line, could sustain steeper 42% to 47% revenue declines due to their higher exposure to intra-Asia trade, which would tumble along with other seaborne trade routes in the region.

Air and Sea Blockade

Invasion isn’t Beijing’s only option. It could opt for an air and sea blockade designed to coerce Taiwan into submission while sidestepping the higher costs and risks of war. China might justify the move with bureaucratic formalities—for instance, announcing a new customs authority to inspect all shipments to and from the island, or wield it as a threat—warning of escalation if Taiwan resists unification on its terms.

A full blockade would disrupt the flow of trade, effectively cutting off the world’s access to Taiwan’s production capacity. It would also likely generate a strong response from the US and its allies who might attempt to break the blockade or loosen China’s grip through punitive economic measures.

For that reason, we assign a low probability to a total blockade. It doesn’t guarantee Chinese control over Taiwan and carries high risk of escalating into conflict. Still, it’s a scenario that Chinese forces practice and that military doctrine suggests is a possibility.

China may initiate the blockade under less threatening appearances, for example, by declaring the air and waters of the Taiwan Strait and around Taiwan subject to Chinese law and customs inspections.

China may deploy its Coast Guard and maritime militia for operations closer to Taiwan, to preserve more legalistic auspices, but would probably keep naval vessels stationed nearby to provide overwatch. The Chinese Navy would likely patrol other key sea lanes surrounding Taiwan, like the Bashi Channel to its south and Miyako Strait to its north.

China would probably similarly patrol the air around Taiwan, and require planes approaching the island to disclose their cargo or potentially to stop in China first for inspection. In a traditional military blockade, Chinese forces would attempt to block most if not all vessels and planes from entering the quarantine area. In a less aggressive scenario, like a customs inspection regime, Chinese forces may selectively interdict vessels.

The economic consequences of a full blockade are severe. For simplicity and comparability with other scenarios, we assume the blockade lasts a year. In reality, the escalation risks and economic impact of a blockade suggest it would be either broken or pulled down much sooner.

For Taiwan, a small open island economy that depends on energy imports and electronics exports, GDP in the first year is down 12.5%. For China, the US and the world as a whole, GDP is down 8.9%, 3.2% and 5.3%, respectively—driven largely by severe disruption to the global supply of semiconductors and to a lesser extent by trade tensions between China and the US and its allies.

Assuming a blockade prevents semiconductors from leaving Taiwan or inputs for making them getting in, chip inventories would deplete within weeks and production lines using chips as inputs would slow globally.

If Taiwan’s fabs remain intact, recovery could begin once a blockade lifts. How quickly the backlog would clear depends on what happens in Taiwan during the blockade. If fabs have stayed idle, possibly because they are unable to import critical inputs, it could take months to restart exports.

Tensions Could Increase

A further ratcheting up of cross-strait and US-China tensions—stopping short of a major crisis—could involve low-intensity clashes, such as an accidental collision between Chinese and Taiwanese forces in the strait.

A gradual erosion of stability, for example through China’s use of gray zone and “lawfare” tactics to exert pressure on Taiwan, is another possibility. These could include expanded attempts to exert control over the waters or airspace around Taiwan and what moves through them.

Either scenario would increase perceptions of geopolitical risk in the strait and could trigger a response from the US and its allies. We model that as a small shock to Taiwan’s trade with the rest of the world and an increase in tariffs between the US and its allies and China. The first-year impact is a 0.6% blow to China’s GDP, and 0.2% for the US and the global economy.

We see this scenario as the most likely of the five we’ve modeled, based on the trajectory of cross-strait frictions and China’s expansive gray zone toolkit.

What If Things Stay the Same?

The status quo in the Taiwan Strait is under pressure but not fully broken. Most in Taiwan prefer the current situation to either a formal declaration of independence (risking a bloody conflict with China) or unification (risking loss of political freedom).

For China, an attempt at forced unification risks failure, which could spell unrest at home, massive economic costs, international opprobrium and the permanent loss of Taiwan. For its part, the US opposes unilateral changes to the status quo, whether that be a declaration of independence by Taipei or an attempt at forced unification by Beijing.

And yet despite the many reasons for maintaining it, the present equilibrium is unlikely to hold in the years ahead, given rising cross-strait frictions and deepening US-China strategic rivalry.

Rapprochement Is Elusive

Rounding out the set of possibilities, we modeled an upside scenario in which Taiwan and China reach an enduring peace, leading to an increase in cross-strait trade and a de-escalation in US-China tensions. This model could take the form of both sides finding a mutually agreeable path to unification, which meets China’s red lines but satisfies Taiwan’s concerns about preserving democracy. Alternatively, it would require one side making major concessions: China walking away from its goal of unification or Taiwan submitting to it.

Either way, this scenario remains highly unlikely. Every Chinese leader since Mao Zedong has made unification a central goal and tied the Communist Party’s legitimacy to achieving it. Earlier leaders such as Deng Xiaoping showed some flexibility on timing and conditions. Xi Jinping hasn’t. Given that precedent, even a future Chinese leader would find it hard to depart from the established framework.

On the other side of the strait, public opinion in Taiwan has hardened against China—particularly after the Chinese government’s crackdown in Hong Kong—making a shift in sentiment equally improbable. In a 2024 survey by Taiwan’s Academia Sinica, only 12.5% of respondents agreed China was a trustworthy country, and 83.4% believed the threat from China had increased in recent years.

Even if unlikely, the scenario provides a useful benchmark, showing the upside that could come from de-escalation rather than confrontation. We model it as an increase in China-Taiwan trade and a reduction in US-China tariffs, resulting in a modest GDP boost for all three economies. Full unification, which we didn’t model, could come with additional complications. For example, if China assumed control over Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, that may lead Washington to extend its export controls to the island.

The outlook for the Taiwan Strait is uncertain. The stakes are clear. Taiwan sits at the center of the semiconductor supply chain and on top of one of the world’s deepest geopolitical fault lines. Our analysis shows just how costly a crisis there could be—for China, the US and the world.

Top photograph: Anti-landing barriers on the Taiwanese islands of Kinmen, across from Xiamen in mainland China. Photo credit: An Rong Xu/Bloomberg

Copyright 2026 Bloomberg.

Topics

USA

China