Introduction

Immigrants, including those on H-1B visas, make significant contributions to the U.S. health care workforce and help to increase its capacity. H-1B workers are foreign workers with temporary approval to work in the U.S. in jobs that require specialized skills or knowledge. The Trump administration has implemented policies that will likely reduce the supply of H-1B workers, including a $100,000 entry fee for new H-1B visas as well as enhanced vetting and “online presence” reviews for all H-1B and H-4 (dependent) visa applications that have led to significant delays in visa processing.

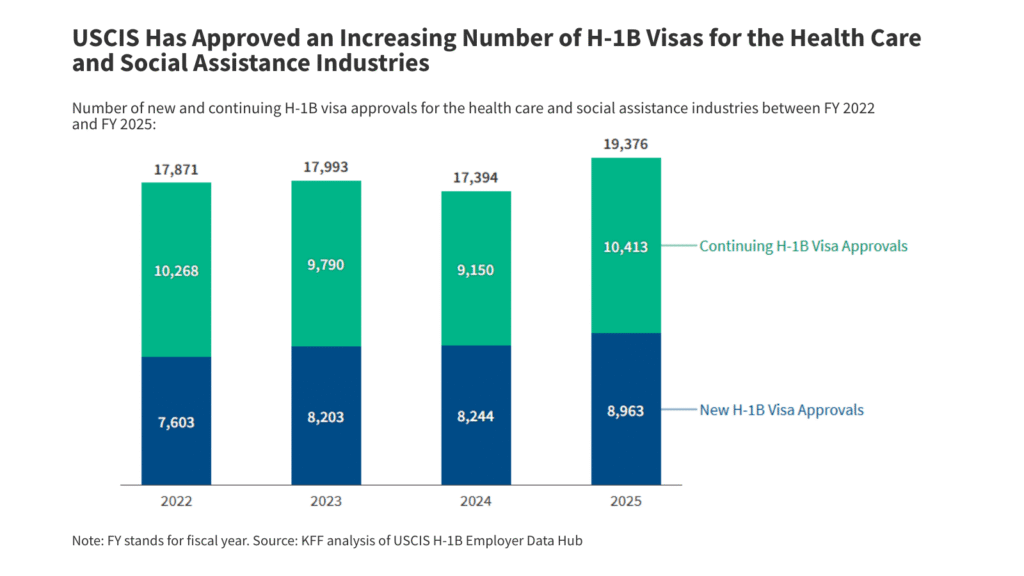

This issue brief provides an overview of the H-1B visa program, analyzes trends in H-1B visa approvals for the health care and social assistance industries using data from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) H-1B Employer Data Hub for fiscal years (FY) 2022-2025, and discusses potential implications of recent policies impacting the H-1B program on the U.S. health care workforce.

The analysis shows that H-1B workers have comprised an increasing role in the health care and social assistance industries in recent years with new and continuing H-1B visa approvals for the health care and social assistance industries rising by 8% between FY 2022 and 2025. As such, reductions in the H-1B workforce would likely lead to gaps in the industries and exacerbate existing health care worker shortages, including in the rural physician workforce.

Background

The H-1B visa program helps supply high-skilled workers to the U.S. workforce, including the U.S. physician workforce, particularly in lower income areas as well as within research universities and university-affiliated medical centers. The H-1B program allows U.S. employers to temporarily employ foreign workers for jobs that require specialized skills or knowledge. According to the American Hospital Association, physicians account for almost half of approved H-1B visas for medical and health occupations. Research further finds counties with the highest poverty levels had a higher percentage of H-1B-sponsored physicians and other health care workers compared to those with the lowest poverty levels (2.0% vs. 0.5%) and that rural counties similarly had a higher share of H-1B physicians and other health care workers than urban counties (1.6% vs. 1.0%). Research universities and university-affiliated medical centers are some of the largest employers of H-1B health care and social assistance workers. In FY 2025, the top three employers of workers with H-1B health care and social assistance visa approvals included Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Tennessee, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The number of new H-1B visas is capped at 65,000 each year with an additional 20,000 visas for those with a U.S. master’s degree or higher, although the cap is typically exceeded via exemptions. The H-1B visa cap of 65,000 was first established in 1990 under the Immigration Act of 1990, although it was temporarily increased from FY 1990-2000 as well as FY 2001-2003 by Congress. In FY 2004, the cap reverted to 65,000, with an additional 20,000 new visas reserved for those with a U.S. master’s degree or higher and has stayed the same since. However, the number of new H-1B visas granted each year generally exceeds the annual cap of 85,000 because of cap exemptions. For example, institutions of higher education, government research organizations, and certain nonprofits are exempt from the annual cap.

The Trump administration has implemented changes that are expected to reduce the number of H-1B workers in the U.S. These changes include a Proclamation issued on September 19, 2025, under which new H-1B visa petitions by employers must be accompanied by a $100,000 entry fee, a move that is being legally challenged by 20 states on the basis that it violates the Administrative Procedure Act. The Department of Labor launched Project Firewall in September 2025, which has led to an increase in random site visits and stricter scrutiny of third-party worksites in an effort to root out H-1B “fraud and abuse.” Additionally, the U.S. Department of State began enhanced vetting and “online presence” reviews of all H-1B and H-4 (dependent) visa applications starting December 15, 2025, which has led to significant delays and cancellations of visa interviews, leading to many H-1B workers getting stuck abroad.

Recent Trends in H-1B Visa Approvals

Based on KFF analysis of data from USCIS, new and continuing H-1B visas for the health care and social assistance industries increased by over 8% from just under 18,000 in FY 2022 to over 19,000 in FY 2025 (Figure 1). The Bureau of Labor Statistics defines the health care and social assistance industries as establishments that provide health and medical care, as well as those that provide social assistance. Examples of such establishments include but are not limited to hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, medical laboratories, home health agencies, and social service centers. In contrast, the total number of new and continuing H-1B visas across other industries fell by 9% from over 420,000 in FY 2022 to about 390,000 in FY 2025.

H-1B workers play a particularly significant role in the health care and social assistance industries in certain states. NY (14%), MA (9%), CA (8%), PA (6%), and OH, TN, and FL (5% each) accounted for over half (52%) of new and continuing H1-B visas for the health care and social assistance industries approved in FY 2025 (Figure 2). These states are home to large research universities and medical centers, which, as noted, are some of the biggest employers of H-1B workers in the health care and social assistance industries.

Implications

These data suggest that H-1B workers have played an increasingly large role in the health care and social assistance industries in recent years, suggesting that reductions in the supply of H-1B workers could leave gaps that exacerbate health care worker shortages. Recent actions by the Trump administration are anticipated to reduce the number of H-1B workers in the U.S., including the new $100,000 entry fee as well as “online presence” reviews for H-1B visa applications. A decline in the supply of H-1B workers in the health care and social assistance industries could disproportionately impact states that employ the largest numbers of H-1B workers, lower income and rural areas where H-1B health care workers often are employed, and smaller employers who would face greater challenges paying the new $100,000 fee. Research universities and university-affiliated medical centers, which are some of the largest employers of H-1B health care workers, also are likely to be disproportionately impacted at a time when they are already facing broader funding cuts. The resulting shortages in the health care workforce are likely to increase barriers to accessing health care, potentially affecting the health and well-being of the population over the long term.

These actions to reduce the number of H-1B workers come against a backdrop of increased immigration enforcement as well as other restrictions on lawful immigration into the U.S. These efforts have reduced the flow of immigrants into the country and have increased fears among immigrants already here. Researchers project that restrictive policies undertaken by the Trump administration could reduce legal immigration into the U.S. by 33% to 50% over four years as compared to FY 2023 levels. Broad reductions in immigrants could particularly affect the health care workforce given the significant role they play as hospital physicians, nurses, as well as direct long-term care workers. These reductions may be compounded by a projected decline in the U.S.-born labor force over the next few decades due to an increase in the share of the U.S.-born population that is over 65 years of age and therefore less likely to participate in the workforce.